Stealing OAuth tokens with a relative wildcard URL

INTRO

In this blog post, I will discuss an interesting security bypass I found which allowed me to leak OAuth access tokens via a postMessage. This bug would've enabled an attacker to connect a victim's third-party account to the attacker's account and perform actions on behalf of the victim and steal some pretty sensitive data. The target website had defenses in place to prevent OAuth tokens from leaking, but I was able to bypass these defenses thanks to a relative wildcard URL. I know what you’re thinking now: “What the hell is a relative wildcard URL??”. This will make more sense as you keep reading ;)

I discovered this vulnerability while participating in a private bug bounty program so I will be using “redacted.com” instead of the actual name of the website.

CONNECTING THIRD-PARTY ACCOUNTS

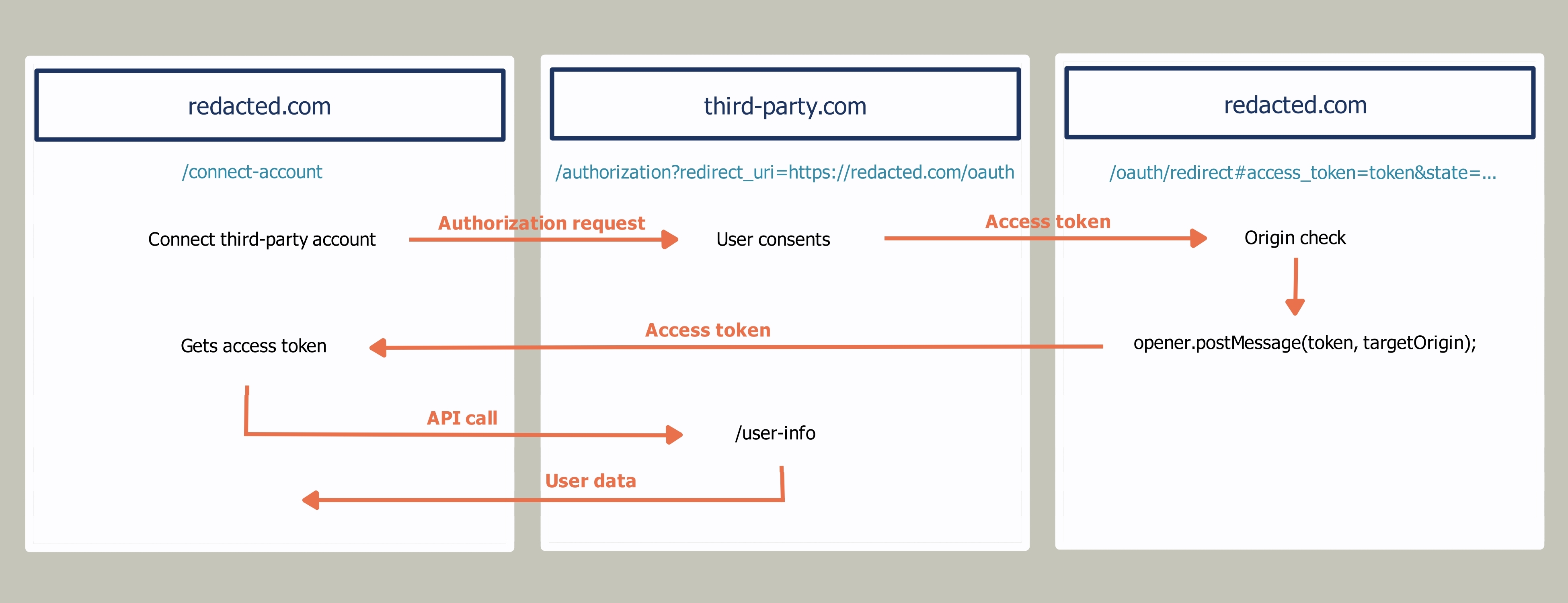

The vulnerability was found in a feature that allows users to connect third-party accounts to their Redacted account. Once a third-party account is connected to their Redacted account, Redacted users can directly send orders to the third-party account, receive data from it, and more. The connection between a third-party account and a Redacted account is established through an OAuth flow provided by redacted.com.

When the Redacted user wants to connect a third-party account to his account, he will first be redirected to the third-party website where he is asked to grant permission for redacted.com to access their data. If the user grants permission, the third-party app sends an access token back to a fixed "redacted.com/oauth/redirect" endpoint, specified in the "redirect_uri" parameter of the authorization request.

After receiving the access token from the third-party app, redacted.com/oauth/redirect will send it back to the page that initiated the OAuth flow via a postMessage(), under the condition that this page is on a redacted.com domain. Validating the target's origin is a necessary step to prevent the access token from being sent to an arbitrary domain, such as an attacker’s website.

Redacted can now use this access token to fetch user data from the third-party app. This flow is called an Implicit OAuth flow since the access token is returned immediately without an extra authorization code exchange step.

THE VULNERABILITY

The vulnerability was found on the redacted.com/oauth/redirect page, which is responsible for receiving the access token and sending it to the Redacted page that initiated the OAuth flow using a postMessage(). Before sending the access token using postMessage(), the page verifies that the message receiver is a Redacted domain. This check is essential to prevent the access token from being sent to an unauthorized domain. However, the implemented check was flawed.

While examining the JavaScript code on this page, I noticed that they were using some unusual methods to verify the target origin before sending the access token. Strange JavaScript code is a hacker's best friend, chances of finding bugs there are often pretty high! Let's take a closer look at the code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

function parseFragment() {

var hash = window.location.hash.slice(1);

var hashMap = new URLSearchParams(hash);

var state = JSON.parse(atob(hashMap.get('state')));

var result = {

state: state,

token: hashMap.get('access_token'),

};

return result;

}

var data = parseFragment();

var targetOrigin = data.state.origin || document.location.origin;

The parseFragment() function extracts two parameters, access_token and state, from the URL fragment (the part of the URL after the # symbol). The value of the state parameter is first decoded from base64 and then converted into a JavaScript object. Finally, the function returns an object containing the access token and the state object. A variable named data is created and assigned the result of calling the parseFragment() function.

The value of data.state.origin is assigned to the variable targetOrigin. However, if data.state.origin is falsy (e.g., null, undefined, or an empty string), the value of document.location.origin (which is "redacted.com" in this case) is assigned to targetOrigin instead. This targetOrigin variable is later used by the postMessage() function, so we'll want to pay special attention to it!

This is already pretty interesting code. The state parameter is an optional parameter in the OAuth flow’s authorization request and is usually used to mitigate CSRF attacks. However, it can be used to store any information since the state parameter that is returned with the access token is expected to be the same as the one you sent in the authorization request. This means that we can set this targetOrigin variable to any value we want through the state parameter in the authorization request. All we need to do is base64 encode the string "{origin: ‘PAYLOAD HERE’}". Let's see how this targetOrigin variable is being validated next.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

function isInternalURL(url) {

var link = document.createElement('a');

link.href = url;

return isInternalHost(link.hostname);

}

function isInternalHost(hostname) {

var baseHostname = window.location.hostname;

var trustLevels = (baseHostname.slice(-1) === '.') ? 3 : 2;

var baseDomainParts = baseHostname.toLowerCase().split('.').slice(-trustLevels);

var domainParts = hostname.toLowerCase().split('.').slice(-baseDomainParts.length);

return baseDomainParts.join('.') === domainParts.join('.');

}

if (!isInternalURL(targetOrigin)) {

throw new Error('invalid origin');

}

message = {

token: data.token

}

opener.postMessage(message, targetOrigin);

This part of the code makes sure that the targetOrigin variable is set to a "redacted.com" domain. The targetOrigin variable will be used by the postMessage() function to determine the message receiver, so this check is essential to prevent the access token from being sent to an unauthorized domain. However, it was flawed...

The code checks whether the targetOrigin is set to a redacted.com domain via the isInternalURL() function. If the check fails, the page throws an error and stops executing. If it succeeds, the access token is sent to the targetOrigin domain. This is where the code started to look a little bit weird to me.

The validation in the isInternalURL() function is done like this:

- First an anchor element is created.

- The anchor’s “href” attribute is set to the targetOrigin value (which we control).

- Finally, the isInternalHost() function basically checks if the hostname of the URL set in the anchor’s href attribute is equal to a “redacted.com” domain.

This means that if we would set the targetOrigin to "https://attacker.com", this code would successfully throw an error since the hostname "attacker.com" is clearly not a "redacted.com" domain and the access token wil not be sent over to the attacker.

However, the developers did not account for one thing here: the magical 'relative wildcard URL'.

I knew that the postMessage() function would only send the access token to me if I could set the targetOrigin to an arbitrary domain OR if I could somehow set it to "*". A targetOrigin of "*" acts as a wildcard in a postMessage() function, which means the message can be sent to any domain.

So what happens if we set the targetOrigin to "*" and the isInternalURL() function tries to validate the hostname by creating the following anchor element:

1

<a href="*"></a>

The result is that “*” is now treated as a directory that is relative to the current page’s URL. Since we’re on the redacted.com/oauth/redirect page, an href of “*” will point to the following URL:

1

https://redacted.com/oauth/*

Great! Our wildcard URL will now pass the check because its hostname is a redacted.com domain and no error will be thrown. Our “*” payload is allowed to be set as the postMessage’s target origin and the access token can now be sent to any domain listening for the message:

1

opener.postMessage(message, "*");

THE ATTACK

To exploit this bug, all an attacker needs to do is trick a Redacted user into clicking on a button on the attacker’s website. This will send an authorization request with the malicious state parameter to the third-party app. The state value needs to be set to "eyJvcmlnaW4iOiIqIn0=", which is the base64 encoded string "{origin: ‘*’}". If the victim is already logged in to the third-party app and has previously given Redacted access permissions, their access token will be automatically sent to the vulnerable redacted.com endpoint. The flawed target origin check on this page will allow to send the victim's access token back to the attacker's domain.

Once the attacker has obtained the victim's access token, he can start the legitimate OAuth flow from his Redacted account and replace his access token with the victim's access token. As a result, the victim's third-party account will be connected to the attacker's Redacted account. The attacker can now access sensitive user data and perform actions on the victim's third-party account that would make the victim lose a lot of money.

CONCLUSION

This was an interesting finding with a pretty high impact. Developers often seem to mess up the combination of OAuth + postMessage(), so I highly recommend you start looking for these kinds of bugs if you haven’t already. Also, remember that OAuth is not only used for logging into applications; other features might also use it. So keep an eye out for authorization requests, typical OAuth parameters like "redirect_uri", "client_id", "response_type", and access tokens being sent around.

I’ll wrap up with a few more general lessons this bug taught me:

Pay extra attention to unusual-looking code. Knowing when code is unusual or not obviously requires some experience, but one way to acquire it relatively quickly is by comparing similar features used in different applications. Compare how applications A, B, C and D implement the same feature and identify the similarities and differences. The differences tend to be the places that are more prone to error (unless everyone is just doing it wrong), so pay special attention to those areas. This way of learning/testing by comparing is especially useful for features using standardized protocols like OAuth.

Be careful when making assumptions during testing. When I first analyzed the JavaScript code that validates the target origin, I immediately dismissed the option of using a "*" wildcard because the code was looking for a URL, and "*" is clearly not a URL, right? However, after failing to sneak in a different domain for a while and examining my input in the developer console, I realized that absolute URLs were not the only available option here. My initial assumption was clearly wrong, and I’m glad that I eventually realized it. The moral of the story is: don’t assume, test and confirm it.

Finally, I’ve also included a list of helpful resources for those of you who want to learn more about OAuth and OAuth vulnerabilities.

- https://developer.okta.com/blog/2017/06/21/what-the-heck-is-oauth

- https://portswigger.net/web-security/oauth

- https://www.oauth.com/

- https://www.rfc-editor.org/rfc/rfc6749

- https://labs.detectify.com/2022/07/06/account-hijacking-using-dirty-dancing-in-sign-in-oauth-flows/

- https://ninetyn1ne.github.io/2022-02-21-oauth-postmessage-misconfig/

- https://ysamm.com/?p=763

- https://book.hacktricks.xyz/pentesting-web/oauth-to-account-takeover

- https://0xn3va.gitbook.io/cheat-sheets/web-application/oauth-2.0-vulnerabilities

- https://blog.securityinnovation.com/pentesters-guide-to-evaluating-oauth-2.0

- https://salt.security/blog/traveling-with-oauth-account-takeover-on-booking-com

- https://blog.dixitaditya.com/oauth-account-takeover